What is Debrucing?

what is debrucing?

Updated with new data and insights, Feb. 9, 2023

“Debrucing” is the act of eliminating the government spending limit and allowing that government to retain and spend all of the revenue it collects under existing tax rates. The revenue cap is part of the Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR) and reduces the state’s ability to raise revenue and invest more funding into the priorities that Coloradans care about.

The revenue cap has been a topic of debate since the passage of TABOR in 1992. The cap has led to an artificial ceiling on public investment in Colorado, and, until 2005, severely limited Colorado’s ability to spend on public programs in economic downturns. Achieved through voter-approved ballot measures, eliminating the revenue cap or debrucing (the term is a nod to TABOR’s author Douglas Bruce) has been considered by many Colorado localities.

In 2005, Colorado voters approved Referendum C, which temporarily lifted the revenue cap and eliminated the ratchet effect. The ratchet effect reduced the revenue cap in tough economic times, and led to lower spending on community priorities. In 2019, Colorado voters voted down Proposition CC, which would have debruced revenue statewide. To date, Proposition CC has been the only attempt to remove the revenue cap at the state level.

what is the revenue cap?

The revenue cap means no matter how much revenue comes into any state or local government in Colorado from taxes paid, that government has a limit on how much money it has available to invest in its residents.

The text of the Colorado Constitution addressing the revenue cap is Article X, Section 20, Subsection 7, and involves three primary components.

- Revenue cap formula: A calculation of how much growth in state spending is allowed in a given year.

- Mechanisms for rebates: If state revenue exceeds a certain threshold, the method and mechanisms used to direct that revenue to some or all of Coloradans.

- Ratcheting effect: An effect that happens in years of slow growth, essentially “ratcheting” down spending growth to the lowest years of state spending, dramatically limiting public spending to recover and match the economy. The ratchet effect was eliminated by passage of Referendum C in 2005.

All together, these components prevent public investment in Colorado to meet a changing economy and provide the vital services needed to keep the state competitive for generations to come. In years of strong economic growth, governments haven’t been able to take advantage of a rising economy and make needed investments.

The formula for the cap boils down to a calculation of inflation plus population growth. Unfortunately, this formula wasn’t designed to match government budgets nor the increased costs in government-provided services.

In terms of population growth, not all populations have the same public service needs. Younger and older people both need a higher share of services — think health care, education, and other targeted programs — than other groups. For example, young Coloradans need investments in child care and education that adults do not. Also, Colorado has a growing number of older residents who rely on significant health care and long-term care expenditures, but overall population growth is not a strong metric for guiding how much revenue is necessary to invest in this particular group.

In terms of inflation, the TABOR formula uses the Denver-Aurora-Lakewood consumer price index (CPI) to account for inflation growth. CPI is typically used to measure how much the costs of goods and services for a family have changed over time. This is problematic in calculating a government revenue limit because CPI doesn’t measure the changes in the prices of goods and services purchased by governments. The inflation for a gallon of milk or a new pair of pants isn’t tied to the price of services like health care or education.

A look at long-term changes in the cost of healthcare – a significant government expenditure – highlight the problems with a reliance on pegging the revenue cap to inflation. Since October 2000, medical inflation has grown 110.1 percent, while the CPI has only increased 71.3 percent over the same time period.

Furthermore, the inflation component lags actual budget decisions. The CPI in 2022 reached a 40-year high, but that inflation figure will affect the fiscal year 2023-24 budget – a time when inflation is expected to normalize. That means that when the budget actually needs room because of inflationary price increases, the formula won’t allow it.

When broken down and combined with other aspects of TABOR, the revenue cap limits government spending without concern for growing economic demands. This is made possible by using a formula that’s imprecise and detached from the needs of the state.

Referendum C proposed a five-year timeout from the revenue cap between fiscal year 2005 and fiscal year 2009 and eliminated the ratchet effect from future revenue cap calculations. Referendum C created a new baseline for the revenue limit that was above the ratchet level, but below the pre-recession TABOR level.

Without Referendum C, lawmakers would have needed to cut the state’s budget by $2 billion, likely by slashing the budgets of healthcare, higher education, senior property tax exemptions, and other important services many Coloradans rely on.

Permanent tax cuts signed in 1999 and 2000, as well as the recession of 2001-2003, which impacted Colorado significantly, were the catalysts for Referendum C. Decreasing state revenue meant many services had to be cut to balance the budget. When the economy recovered, revenues started to increase to pre-recession levels.

However, since the revenue cap was based on the most immediately prior revenue, the state’s revenue cap would have been pegged to those new lows. The result would have been disastrous and would have had a profound long-term effect. This led to the development of and passage of Referendum C.

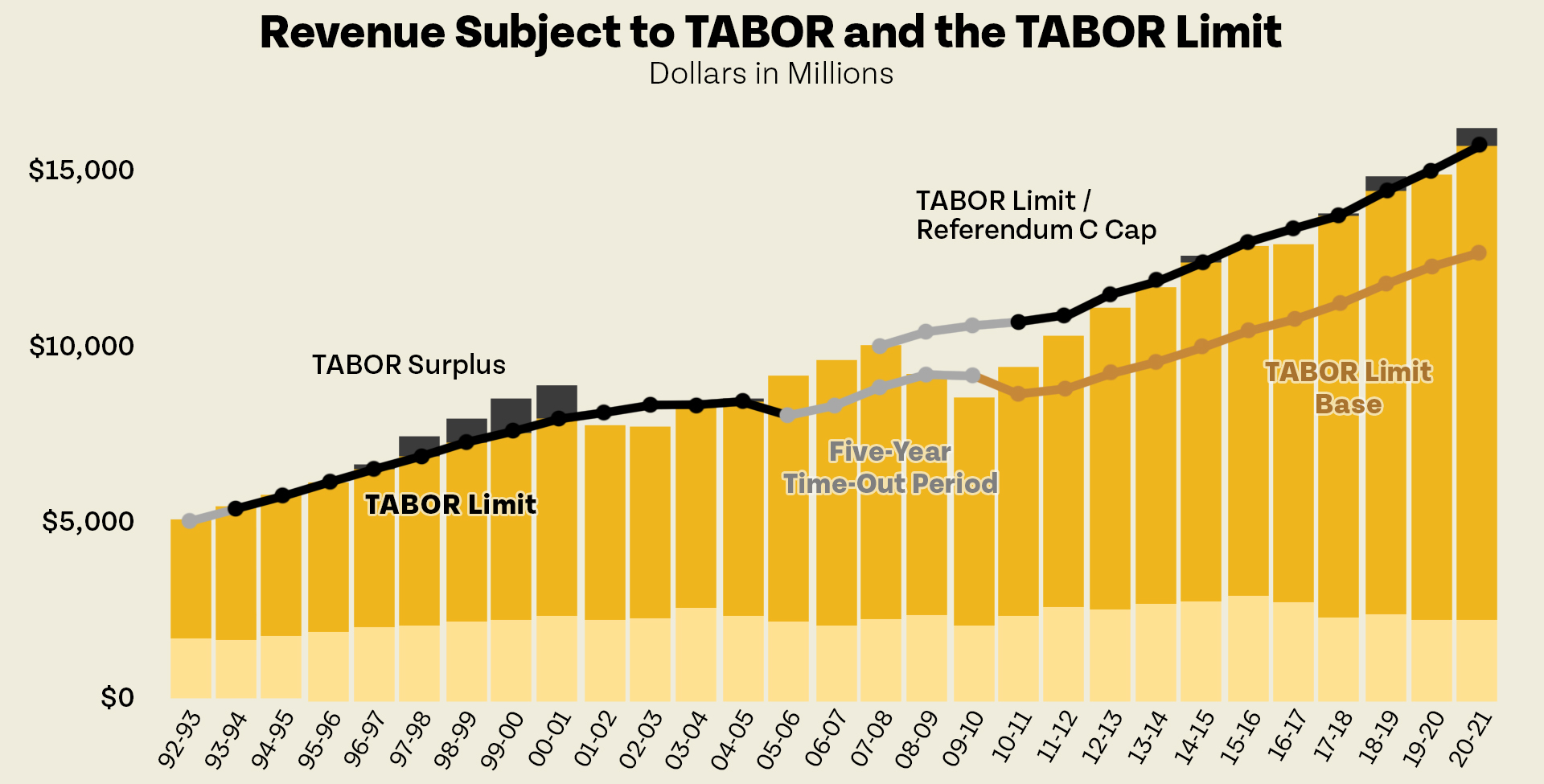

Referendum C did two things: First it gave the state a five year catch-up period, during which the state could keep all revenues and spend them on K-12 education, higher education, health care, and transportation. The second thing it did was eliminate the ratchet effect by calculating the revenue limit on a continuous trajectory of the population and inflation based upon the highest revenue point during that five-year time out. As seen in the chart below, just because revenue dips in one year, the revenue limit is not attached to that new low. Instead, it is based on inflation and population, year after year, on the revenues from 2007-2008. By passing the referendum, voters eliminated the ratchet and, as the Denver Post put it in endorsing the measure, “increase[d] state revenues by $3.6 billion by 2010 — at which point the state’s authorized revenue will still be $200 million below the level authorized by TABOR itself if there had been no recession.” This was all done without raising taxes. In fact, because the economy recovered better than anticipated, revenue actually increased by $5.7 billion.

Source: Colorado Office of the State Controller and Legislative Council Staff

Debrucing Across Colorado

Because TABOR applies to all governments and taxing districts in Colorado, no matter how big or small, the question of eliminating or changing the revenue cap has come to the voters many times.

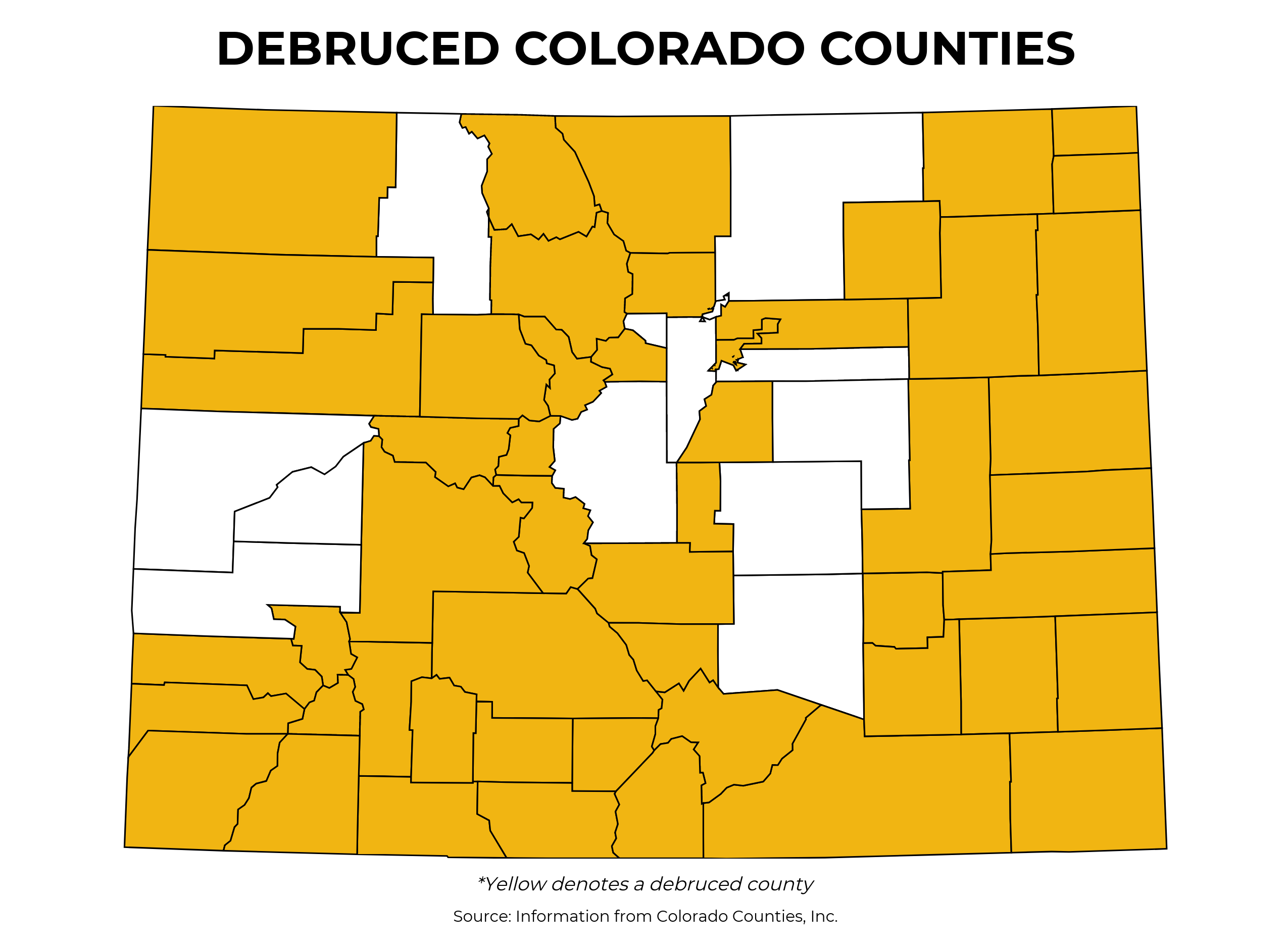

Debrucing appeals to a wide swath of voters and constituencies. In fact, 51 out of the 64 counties in the state, 230 out of the 274 municipalities, and 177 out of 178 school districts, have debruced since TABOR’s inception in 1992.

In 2019, many groups and organizations that disagree on many aspects of public policy came together to endorse the statewide debrucing measure known as Proposition CC. Those groups included K-12 and higher education groups and associations across Colorado, the Colorado Contractors Association, state and municipal chambers of commerce, the Colorado Hospital Association, the Colorado Municipal League, county commissioners, and former Republican and Democratic elected officials. They all felt that Colorado should be able to use lawfully collected tax dollars to improve public investment and support communities across the state. Nevertheless, Proposition CC was rejected by a 54-46 percent margin.

In 2019, many groups and organizations that disagree on many aspects of public policy came together to endorse the statewide debrucing measure known as Proposition CC. Those groups included K-12 and higher education groups and associations across Colorado, the Colorado Contractors Association, state and municipal chambers of commerce, the Colorado Hospital Association, the Colorado Municipal League, county commissioners, and former Republican and Democratic elected officials. They all felt that Colorado should be able to use lawfully collected tax dollars to improve public investment and support communities across the state. Nevertheless, Proposition CC was rejected by a 54-46 percent margin.

TABOR refunds are structured through statutory law and have shifted over time, averaging anywhere from $15 to $750 per taxpayer at the state level. At various points, the refunds have been used to further policy objectives, such as paying the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) through the refund or providing refunds for capital gains taxes and purchasing pollution control equipment. The current TABOR refund law has a number of allowable uses, but only two established mechanisms currently in statute:

- Senior Homestead and Disabled Veteran Property Tax Exemption: When a refund is triggered, the first people to receive them are those who are eligible for the Senior Homestead and Disabled Veteran Property Tax Exemption. Once that is paid out, the next level is triggered.

- Sales Tax Refund: All taxpayers are eligible for this refund. The amount refunded is done in tiers, depending on income levels. So, wealthy Coloradans — those making more than $225,000 per year — see a larger refund than those who earn less, all the way down the income ladder.

A temporary income tax rate reduction to 4.5 percent was the third mechanism from 2005-2022 but was only triggered in fiscal year 2018-19. When voters passed an income tax rate cut to 4.4 percent in the 2022 elections, it made the temporary rate cut inapplicable. However, when it was used as a mechanism, the income tax rebate mechanism delivered a disproportionate amount of the revenue over the cap to the wealthiest Coloradans.

Some other ways of distributing money over the revenue cap have been used in recent years.

- Flat Rebates: In 2022, the legislature passed a one-time law to change the sales tax refund mechanism. Instead of six tiers based on income, it became a single tier, where every taxpayer got the exact same refund, regardless of how much money they made in the previous year. That amounted to $750 per taxpayer. That was hundreds of dollars more – compared to the six-tier mechanism – for low- and middle-income Coloradans, and nearly a thousand dollars less for the wealthiest in Colorado.

- Property Tax Backfill: The legislature also used the revenue over the revenue cap to backfill local government revenue after decreasing property assessment rates. Because lowering assessment rates would decrease local property tax revenue, the state stepped in to make those local governments whole, using TABOR refund dollars to do it.

When voters agree to lift the revenue cap, they forgo the opportunity for individual rebates, and instead allow the governments to put revenue toward supporting important services used by many Coloradans.

Beginning in the mid-1990s, TABOR rebates were an annual occurrence for half a decade. Those were boom years for Colorado and many parts of the country, so the state government collected a lot more revenue than it could spend, due to the revenue cap. As a result, there was a lot of money sent back in taxpayer rebates. Over those five years more than $3.37 billion in rebates were sent, averaging nearly $200 a year per taxpayer.

More recently, Colorado has seen consistent and large amounts of revenue above the statewide cap. From FY 2017-18 through FY 2021-22, Colorado sent $4.69 billion to taxpayers in revenue above the cap – and this includes FY 2019-20 when the COVID-induced downturn forced significant budget cuts, leaving no money above the cap. Legislative Council Services (LCS) is projecting $2.47 billion in FY 2022-23 to be rebated to Colorado taxpayers.

In FY 2023-24 and FY 2024-25, TABOR rebates will be smaller, in large part because Propositions 121 and 123 – which lowered the income tax rate from 4.5 percent to 4.4 percent and put $300 million of General Fund money into housing affordability programs, respectively – will cost the General Fund about $700 million annually. In total, those two fiscal years are projected to have $2.9 billion over the cap.

If LCS projections come to pass, then Colorado will have sent more than $7 billion from 2017 through 2023 to taxpayers instead of investing in communities and important programs like K-12 education, health care, and transportation.

Every year the Legislative Council Staff (LCS), a nonpartisan research arm of the state legislature, releases budget and economy outlooks to help the legislature decide what future budgets should look like. With these is a projection of how much revenue is coming into the state and how that interacts with the revenue cap and TABOR rebates.

According to LCS projections, over four years, starting in fiscal year 2018-19, the state of Colorado will be over the revenue cap by a combined $970.2 billion. This will trigger rebates for all four years. For low-income families, that means about $30 to $50 in TABOR rebates in total, while wealthy Coloradans making more than $225,000 annually could see rebates of $750 over tax years 2019 and 2020.

The state legislature in 2019 referred a measure to be put to the voters in November 2019. Prop CC asked voters to decide whether the state should permanently debruce by eliminating the revenue cap to retain and spend all revenue that comes into Colorado. The money in excess of the cap would have gone to K-12 public education, higher education, and transportation.

The legislature also passed a bill that would go into effect if voters approved Proposition CC. HB19-1258, Allocate Voter-Approved Revenue for Education and Transportation, is very specific about how the money is to be spent, with an even amount going to each priority.

- K-12 Public Education: One-third of revenue over the cap will go to public education on a per-pupil basis. It can only be used for non-recurrent expenses — think capital improvements — and cannot be part of the district reserve.

- Higher Education: One-third of the revenue will go to higher education on a per-pupil basis with the same restrictions as the K-12 education revenue.

- Transportation: One-third of the revenue will go to the Highway Users Tax Fund. Of this revenue, 60 percent will be allocated to the state highway fund, 22 percent will go to counties, and 18 percent will go to cities and unincorporated towns. Of the money going to the state highway fund, at least 15 percent must go toward transit and transit-related improvements.

These three issues are consistently among the most important funding for Coloradans and will see an important increase if voters approve statewide debrucing.

Colorado can consider other options

Now that Colorado’s state spending is up against the TABOR ceiling, and local tax burdens are now a part of the state conversation, how Colorado uses the TABOR surplus has become larger and a more pointed conversation at the capitol.

The rules Colorado has set up must stand up not just in good times, but in bad times as well. If total state revenue is reduced, what programs and services are the most important to save? For many, education is at the top of the list. Proposals that “debruce” state tax revenue to fund Colorado schools and their teachers have bubbled up at the state Capitol, but is “debrucing” even enough?

To rise to the 25th ranked state in per-pupil funding for K-12 and higher education, Colorado needs to invest $1.5 billion more in those programs. According to LCS projections, this constitutes all revenue above the FY 2023-24 cap. Notably, this would leave no additional funds for the many other unmet needs across the state.

Regardless of whether the 1992 author of TABOR could envision the kind of inadequacy and inequality of Colorado’s current tax code, Colorado legislators in 2023 must include the TABOR surplus as part of their annual budget conversation. “Debrucing” is just one of the options on the table.