TABOR: Restrictive Tax Policy Limits Colorado’s Potential

The Taxpayers Bill of Rights, known as TABOR, is a constitutional amendment passed at the ballot in 1992. It has affected nearly every aspect of Colorado’s tax and fiscal system since then. It is considered by some to be the strictest spending and tax law in the country. Proposition A — which was the shorthand for TABOR in 1992 — passed with a little over 800,000 votes, or 53.7 percent. For context, a statewide measure that passed in 2022 passed with 1.2 million votes garnered 52.6 percent of the vote. This shows the number of Coloradans who were not able to vote in 1992 who can now. Many Coloradans never had to understand or read up on TABOR because they did not live in the state or were not eligible to vote when the issue was being debated.

TABOR: Tough to modify and broadly applied

Changes to TABOR are procedurally difficult to qualify and pass. Since 1992, ballot regulations for Colorado have changed and constitutional amendments require a higher signature threshold from around the state. If adding language to the constitution, as opposed to just removing clauses, voters must approve the measure with at least 55 percent.

TABOR applies to every government in Colorado, including city and county governments, special districts, and the state itself. All governmental budgets and tax policy have to adhere to the strict particulars of the constitutional amendment.

TABOR’s difficult choices are not accidental

The combination of the individual aspects of TABOR forces difficult fiscal policy choices, as the trade-offs all have consequences. This was intended by the authors of the amendment, who state in the text: “Its preferred interpretation shall reasonably restrain most the growth of government.”

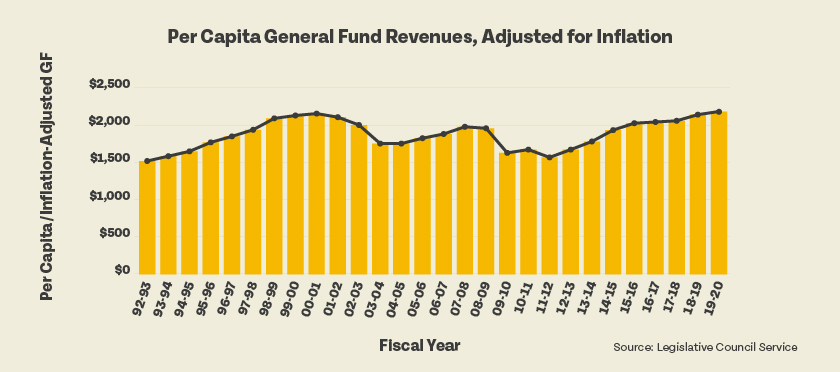

That has borne out in reality, as Colorado’s statewide discretionary budget – known as the General Fund – has barely grown since the FY 2000-01, on a per-capita and inflation-adjusted basis. This makes any ability to invest in communities difficult, and forces reductions in other programs, reforming the overall spending cap, or a vote of the people to make real fiscal change across Colorado.

TABOR’s reach

TABOR contains many provisions, but the parts that most affect Coloradans are:

-

- Any tax policy change that increases revenue for a government must be voted on at the ballot;

-

- Government spending is limited by a formula (i.e, state government spending can only increase by population growth plus inflation) and any tax revenue collected over that formula has to be sent to taxpayers;

-

- Certain taxes are prohibited, such as real estate transfer taxes, local income taxes, and statewide property taxes. Also, all income has to be taxed at the same rate, mandating a flat income tax.

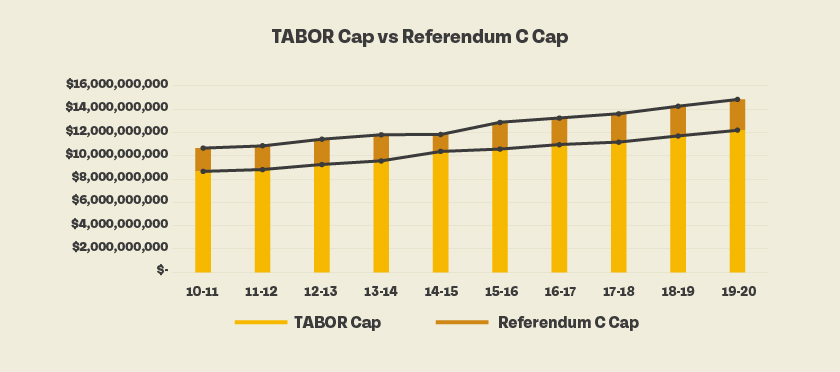

While changes to the actual TABOR amendment are difficult, there have been changes in how the amendment is interpreted and implemented over the past three decades. For instance, most local governments have shed the formula for government spending – commonly known as Debrucing, named after the author of TABOR, Douglas Bruce. Debrucing allows governments to spend all of the tax revenue collected. At the state level, Colorado voters reset the statewide spending cap with the voters’ adoption of the bipartisan Referendum C initiative in 2005.

In addition to changes made by voters, there have been numerous court decisions clarifying questions around the amendment. Many of these decisions have had real impacts on how Colorado navigates the constraints imposed by TABOR.

What was Referendum C?

Referendum C was backed by Republican Governor Bill Owens and many members of the Colorado General Assembly in 2005. The measure was brought forward after several years of declining tax revenue – a consequence of tough national economic conditions at the beginning of the millennium combined with statewide income tax rate cuts that preceded the economic downturn – that forced hundreds of millions of budget cuts that harmed Colorado communities. Coloradans voted in favor of Referendum C in 2005. There were two major reforms contained within Referendum C:

-

- A five-year timeout from the spending cap in TABOR, after which the cap would reset to the highest revenue year within the timeout;

-

- Eliminating the “ratchet effect” – a provision that tied the state budget’s spending cap to the previous year’s budget, even if that number was a decrease in total revenue. The “ratchet effect” effectively forced budget decreases over time, even if tax revenue significantly outpaced previous years’ numbers.

One consequence of the timing of Referendum C is that during the five-year timeout, the Great Recession severely reduced tax revenue for a prolonged period of time. So the TABOR cap reset did not shift upward quite as much as was anticipated in 2005. That consequence led to less community investment than envisioned by the proponents of Referendum C.

TABOR: Voting on Tax Policy Changes

Starting November 4, 1992, districts must have voter approval in advance for:

(a) …any new tax, tax rate increase, mill levy above that for the prior year, valuation for assessment ratio increase for a property class, or extension of an expiring tax, or a tax policy change directly causing a net tax revenue gain to any district.

One of the most well-known parts of TABOR is that voters have to approve tax policy changes that result in a revenue increase. This encompasses much more than just tax rate increases, however. As TABOR states, voters must approve “any new tax, tax rate increase, mill levy above that for the prior year, valuation for assessment ratio increase for a property class, extension of an expiring tax or a tax policy change directly causing a net tax revenue gain.” This plain text shows that any time a government wishes to raise revenue through a change in taxes in order to fund education, health care, transportation, or any other valuable program, voters must approve that prior to the tax change being enacted.

As a state, Colorado has not raised income or sales tax rates since the inception of TABOR, but the state has cut the income tax rate multiple times. Additionally, Colorado has passed certain kinds of statewide revenue initiatives. Some examples:

-

- In 2013 voters approved marijuana taxes through Proposition AA.

-

- In 2020, Colorado voted to approve Proposition EE, which raised taxes on nicotine and tobacco products in order to fund a universal pre-kindergarten program across the state.

-

- In 2022 Coloradans voted in favor of Proposition FF which raised taxes on taxpayers with an income over $300,000 annually in order to fund free meals for all Colorado public school students.

TABOR requires vote to keep “excess” revenue

Another TABOR requirement is that if revenue projections on a ballot measure are lower than the actual revenue collected, voters have to approve retention of the extra revenue in a later election. This happened when marijuana taxes came in above projections after 2013, leading to Proposition BB in 2015 to approve that increase. In 2023, voters will be asked to approve the extra revenue resulting from Proposition EE, in a similar fashion.

While the state has not passed many tax increases, it is much more common at the city, county, and special district level. For example, from 2003-2021 there were 58 questions in Adams County about increasing property or sales taxes and 31 of them passed. These included ballot questions from special districts, cities within Adams County, and the county itself.

TABOR does not ban tax increases, but it does take fiscal decisions out of the hands of our elected representatives and leave major fiscal decisions with voters. There is also very proscribed language – uppercase and bolded wording on the total amount of revenue raised – and bans on certain types of taxes that bias the process against specific taxes.

TABOR’s spending cap

The maximum annual percentage change in state fiscal year spending equals inflation plus the percentage change in state population in the prior calendar year, adjusted for revenue changes approved by voters after 1991. Population shall be determined by annual federal census estimates and such number shall be adjusted every decade to match the federal census.

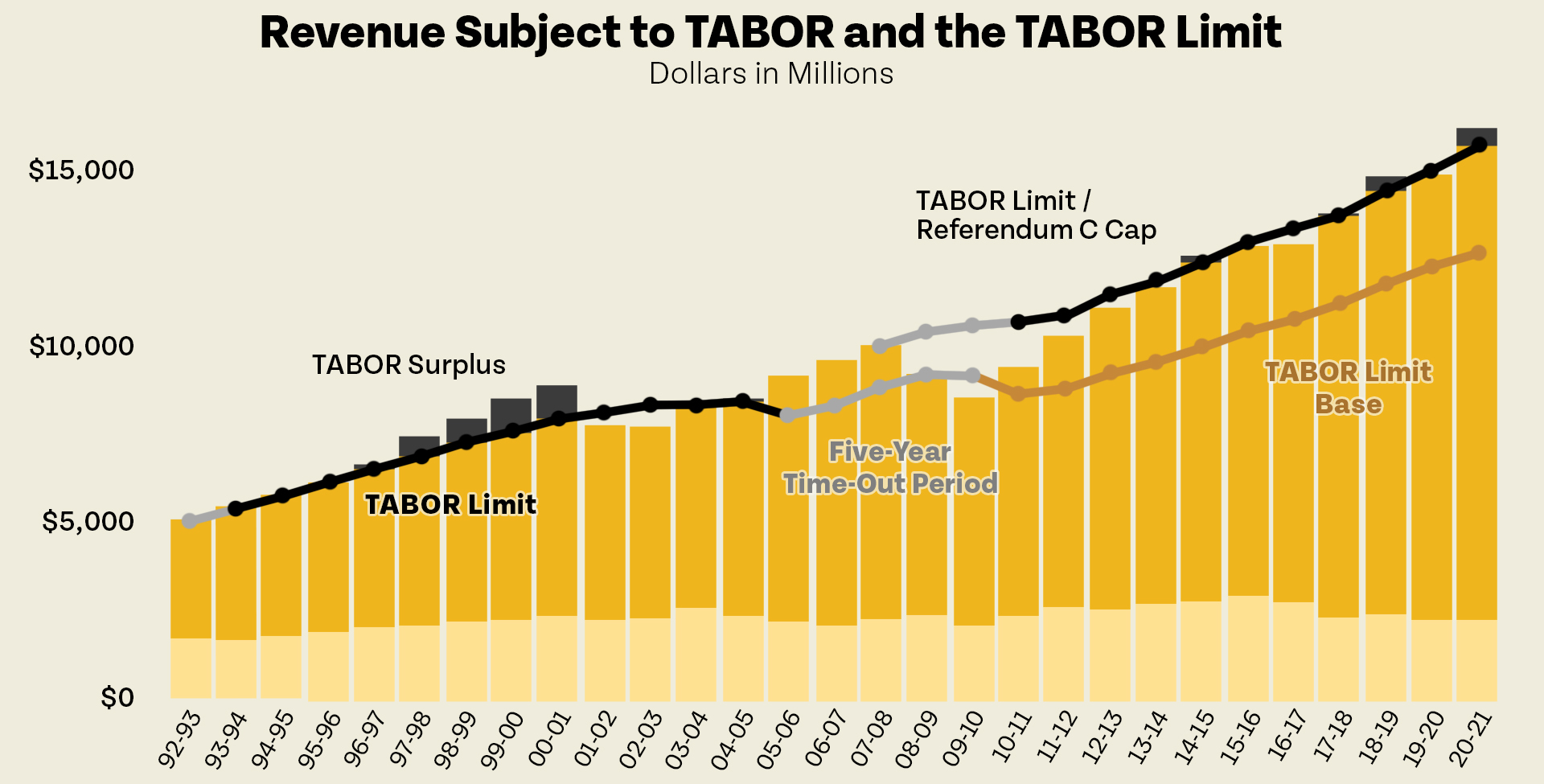

Colorado’s budget is bound by a formula that restricts how much the state is allowed to spend. The formula is the previous year’s revenue plus population growth and inflation. So if Colorado’s population grew by 2 percent and inflation was 3 percent, then the budget can grow by 5 percent. If the government collects money above this cap, it must be sent back to taxpayers. This has happened several times as seen in the chart below. Studies and research have shown that this formula has flaws, specifically that the growth in the formula does not actually reflect the growth in the needs of a statewide population, nor the unique costs of running a government.

When determining revenue subject to the limit, it is important to note that tax credits and deductions reduce the amount of money collected. When Colorado is over the spending cap, tax credits and/or deductions reduce the “surplus” of revenue that Colorado has to send to taxpayers.

The surplus revenue – which is shorthand for revenue over the TABOR cap – has to be sent to Colorado taxpayers. The legislature has wide discretion, as will be discussed below, on how this money is sent back to taxpayers, whether through tax cuts, tax credits, checks to taxpayers, or even money to reimburse local governments for property tax cuts.

TABOR “surpluses” have increased dramatically

Recently, surplus revenue has increased dramatically, as fiscal years 2021-22 and 2022-23 have surpluses over $3 billion, with billions more projected in 2023-24 and 2024-25. While the state has clear needs that could use billions of dollars of investment, TABOR’s rules on spending make funding those needs difficult without a vote of the people.

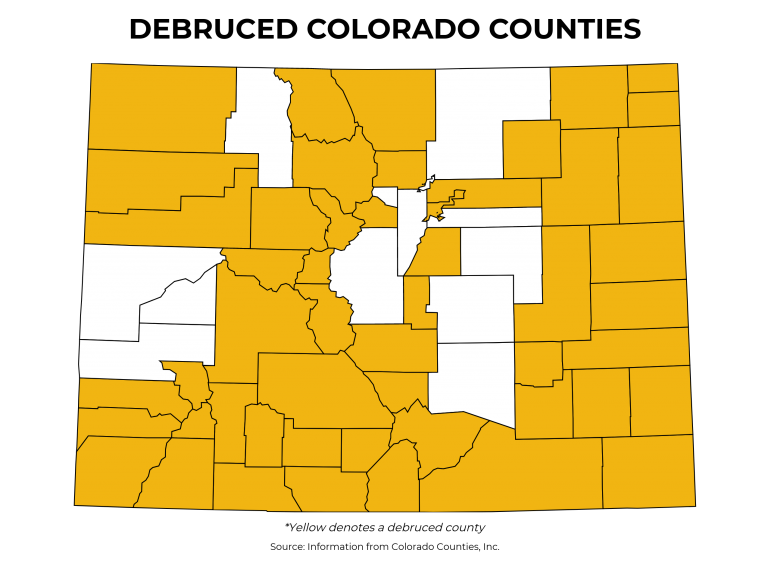

For most local governments, TABOR spending caps no longer apply, as voters have eliminated them. Fifty one of the 64 counties in the state, 230 of the 274 municipalities, and 177 of 178 school districts, have debruced – eliminated the spending cap – since TABOR’s inception in 1992. In fact, according to the Colorado Municipal League, cities have passed debrucing-related measures at a rate of 86.6 percent from 1993-2020, with a total of 503 passing.

Voters have shown that they are generally in favor of removing spending caps from their city and county budget, but that has yet to translate to statewide measures since 2005, when voters amended TABOR to reset the spending cap at a higher level through Referendum C.

How are TABOR “surpluses” distributed?

If revenue from sources not excluded from fiscal year spending exceeds these limits in dollars for that fiscal year, the excess shall be refunded in the next fiscal year unless voters approve a revenue change as an offset.

The legislature has wide discretion on how to allocate revenue over the spending cap, as long as it is not invested in governmental programs. Tax credits and deductions, income tax cuts, property tax reimbursements, and checks have all been used as methods of sending money back to taxpayers.

The first way that money is sent to taxpayers is reimbursing local governments for the Senior and Disabled Veteran Homestead Property Tax Exemption. Generally around $160-170 million, this mechanism has been in place since 2017 and gives property tax exemptions to older adults and disabled veterans who have owned their home for at least 10 years. Because local governments rely on property taxes to fund many of their services, the state reimburses the amount of property tax revenue lost as a result of the Senior and Disabled Veteran Homestead Property Tax Exemption.

Prior to 2022, some of the surplus money was rebated through a temporary reduction in the income tax rate. Proposition 121, however, permanently reduced the tax rate below what was specified as part of the rebate mechanism. As a result, temporary tax rate reductions are no longer part of how TABOR refunds are sent back to taxpayers.

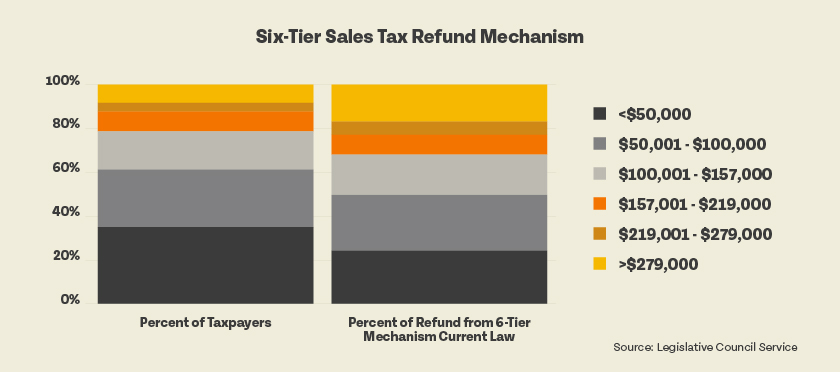

TABOR and the six-tier sales tax rebate

As of 2023, the Six-Tier Sales Tax rebate mechanism is the other primary way, besides the Senior Homestead Exemption, that billions of dollars have been sent to taxpayers. The Six-Tier Sales Tax rebate – commenced in the late 1990s based on research that showed higher earners pay more sales taxes than lower-income Coloradans – is slightly regressive, giving more money to high-income Coloradans than lower-income Coloradans. However, in 2022 the legislature temporarily eliminated the Six-Tier Sales Tax mechanism in favor of the same amount sent to all taxpayers. This change eliminated the prior regressivity in how TABOR rebates are refunded. The legislature has the opportunity to continue that trend, if it so chooses.

TABOR and the senior homestead exemption

Finally, similar to the mechanism for the Senior Homestead and Disabled Veteran Homestead Property Tax Exemption, in 2022 and 2023, the governor and the legislature allocated some of the surplus revenue to reduce property taxes. The surplus money was used to backfill local governments property tax revenue lost due to the property tax cuts.

In future years, if voters approve of a ballot measure in November 2023, more surplus revenue will be used to supplement county governments who will lose revenue due to property tax cuts. However, the catch is that the backfill will only be available in full to those counties that have eliminated their spending cap. As mentioned above, there are 13 Colorado counties – including Denver Metro counties like Arapahoe County and Jefferson County – that have yet to Debruce, and could lose out on state revenue if they keep their spending cap into the future. This is because a specific provision was written into the ballot measure stating that the state will not send money to local districts that have exceeded their spending cap. If this had not been done, local districts that have not Debruced would have had to send state money to local taxpayers as rebates.

Conclusion

TABOR has been in place in Colorado for over 30 years. While there have been small reforms to try and make it work better for the state, it is clear that in many ways the amendment is working as intended in reducing government investments and forcing the underfunding of many important programs throughout Colorado.

Colorado is less equipped to respond to the needs of its people, compared to many other states, because of the rigidity and constraints imposed by TABOR. Thirty years later, Colorado has grown, changed, adapted, and had many successes, but the 1992 election still controls what Colorado can do, in many ways, and is a significant part of every fiscal policy decision in the state.

While every government has to abide by the rules of TABOR, 51 out of 64 counties, 230 out of 274 municipalities, and 177 out of 178 school districts have eliminated the spending cap through a vote of their constituents.