A Year of COVID: What We Learned About Education

Our education system was unequal before COVID-19. However, the pandemic has exacerbated the disparities that previously existed. Low-income and Coloradans with less education have faced higher rates of job loss, leaving the stakes of receiving education higher than ever.

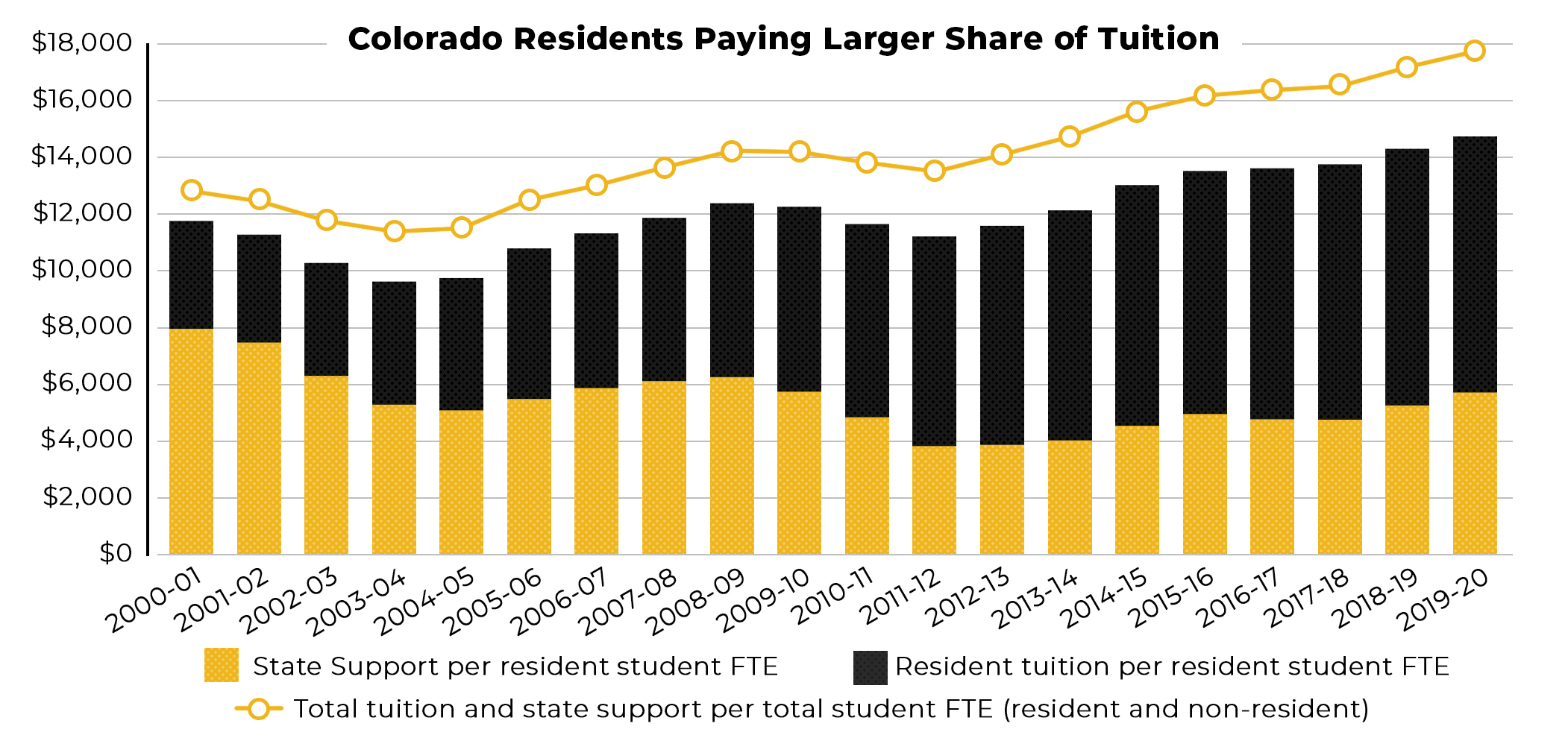

During the last recession postsecondary institutions typically saw boosted enrollment, as job losses encouraged people to attain new skills and delay job-seeking during a time of high unemployment. Simultaneously, as institutions saw increased demand, local and state governments had to cut funding for postsecondary institutions. Thus, the very system intended to improve economic opportunity was rendered increasingly inaccessible to those that most needed it.

Postsecondary education should be the most promising vehicle for upward mobility. Over time in the United States, it has only become accessible to average Americans at a ballooning cost, subsidized by student loans. This has engendered a crisis that is paralyzing millions of Americans under the burden of student debt.

Now, COVID-19 has shown how our model for postsecondary education doesn’t serve the majority of Americans. COVID-19 resulted in the usual dramatic budget cuts to postsecondary education. It also resulted in a decrease in tuition revenue because Coloradans either needed to work or were unwilling to risk exposure or pay the high cost of tuition for an online-based education. While postsecondary institutions try to survive the dual-hit of decreased enrollment and decreased state support, we must collectively contend with the reality that our education system needs to be overhauled. It must center equity and become the promised vehicle for upward mobility that it is vital to our nation.

Education: The Great Inequalizer

Inequities in access to education have shown that education is not living up to its promise as the great equalizer. While legal remedies helped redress some of the overt modes of oppression, indirect barriers, such as the use of standardized tests in college admissions that largely benefit white, wealthy families, continue to lead to less access to postsecondary education for students of color.

Racially driven achievement gaps are well documented. White students continue to have higher rates of opportunity across the system, from high school graduation to postsecondary matriculation. Historical policies, like redlining, compound on more subtle, but still systemic, racist policies such as school financing models.

Even as these structural barriers to access are addressed, a new barrier takes prominence: cost. For postsecondary institutions, as universal access decreases, the wealth of upper-class Americans is increasingly used to prop up a system that has faced growing disinvestment from state governments. Amidst this, low- and middle-income Americans have had to turn to student loans to be able to afford access to institutions that promise to improve their opportunity and economic outcomes.

Colorado ranks 47th nationally in terms of the postsecondary attainment gap between Hispanic and white Coloradans. As of 2017, there was a 35-percentage point gap between white and Hispanic postsecondary enrollment. Historical and contemporary practices continue to engender disparities in outcomes. Meanwhile, our state’s economy requires higher levels of education for good jobs.

A Year of Tough Lessons

COVID-19 disrupted nearly every aspect of life. However, as the Brookings Institute notes, its disruptions to education were some of the most notable and most costly. Learning losses during the pandemic will cost trillions in future lifetime earnings. Yet, across the education spectrum, affluent families quickly found workarounds.

Child care access remains inequitable. Limited access worsened the economic outcomes for women, who have had to fill these gaps, erasing decades of progress towards pay equity. In K-12 education, “learning pods” sprouted across the country, for families who could afford a full-time tutor. They helped mitigate risk of exposure and saved students from the inconsistency and growing pains of remote learning. Meanwhile, middle- and upper-income students who can afford to not work while attending college full time can continue virtually attending classes during the pandemic.

However, for many, the costs, barriers, and risks are too high, especially as family members may face unemployment. Alarmingly, most of the decrease in enrollment seen in the fall of 2020 was in community colleges. These institutions disproportionately serve low-income students and communities of color.

COVID-19 has shown a system that requires someone to not work full-time for multiple years to earn a credential simply isn’t accessible to the vast majority of Americans. Too many are taking on the risk of student loans in the hopes of improving their outcomes to have a fighting chance to fully participate in the economy. To build a system for Americans today means redesigning postsecondary education so that equity and economic opportunity are central to its raison d’être.

Building an Equitable Future

Failure to make postsecondary education a true engine for upward economic mobility for all will make our society increasingly inequitable while also threatening to leave our workforces underprepared for the future of work. Affordability and access cannot be mere buzzwords, but rather the driving force behind our policymaking. We are failing generations of Americans if pursuing a postsecondary credential leaves someone with more debt and the same job prospects they had before.

Our education system needs to be accessible and lead to better opportunity. To this end, postsecondary education needs to be more affordable and align to the needs of industry. One clear priority has to be increasing state support for postsecondary education. Here are four big ideas for how we can begin on this pathway towards building a system that works for the many, not the few:

- Make community college free for all.

- Ensure that short-term credentials can be easily earned, beginning in high school, with on-ramps through our community colleges. These credentials should align with industry needs, and stack into longer term credentials at two- and four-year institutions.

- Help address the indirect costs of college by having flexible grants and scholarships.

- Value the skills and learning that students already have through greater access to prior learning assessments.