Colorado Housing Primer

Click here for printer friendly document

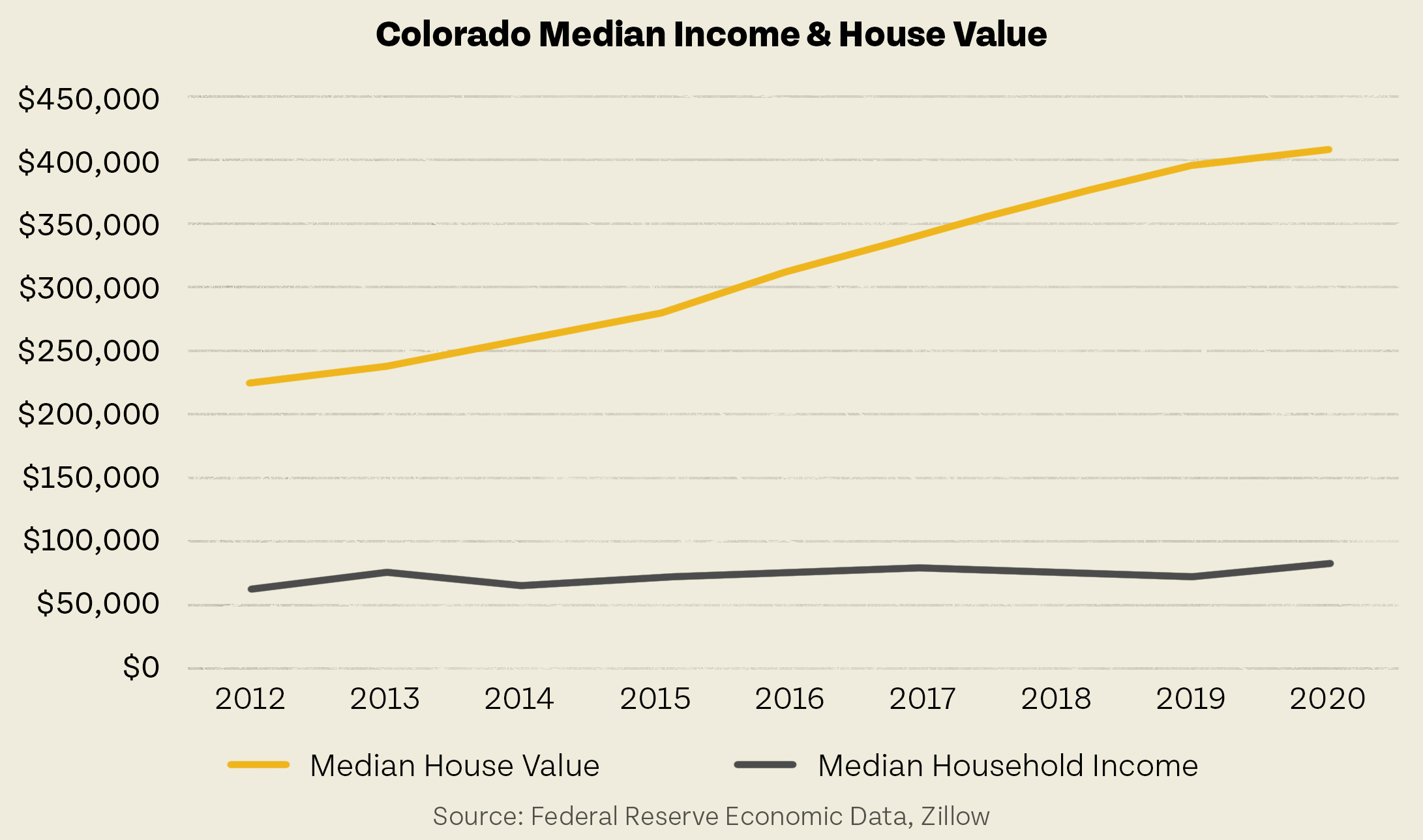

An expanding economy and growing state continue to leave behind many, as house prices and rents have surged over the last decade–a result of a statewide housing shortage combined with increased demand to live in Colorado. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, Colorado is the 9th least affordable state for housing. At the state level, for a minimum wage earner to afford a two-bedroom apartment, they would need to work 89 hours per week. While the state’s GDP now exceeds its pre-pandemic level, lower-wage jobs are yet to recover. Despite major housing legislation in the 2021 legislative session, Colorado does not have enough affordable and available housing for low- and middle-income Coloradans with wages unable to keep up with shelter prices.

As we’ve often shared here, there are many Colorados and there are many housing markets within the state. Too often we talk only about housing for property owners. Conversely, when housing analysis shifts to renters, it focuses predominantly on the rental market in Denver. This analysis seeks to break down the housing market county-by-county as well as by income and racial categories. As housing inequality grows in our state, The Bell wanted to break down the causes, trends, and impacts of the affordable housing crisis in Colorado.

Housing across the state

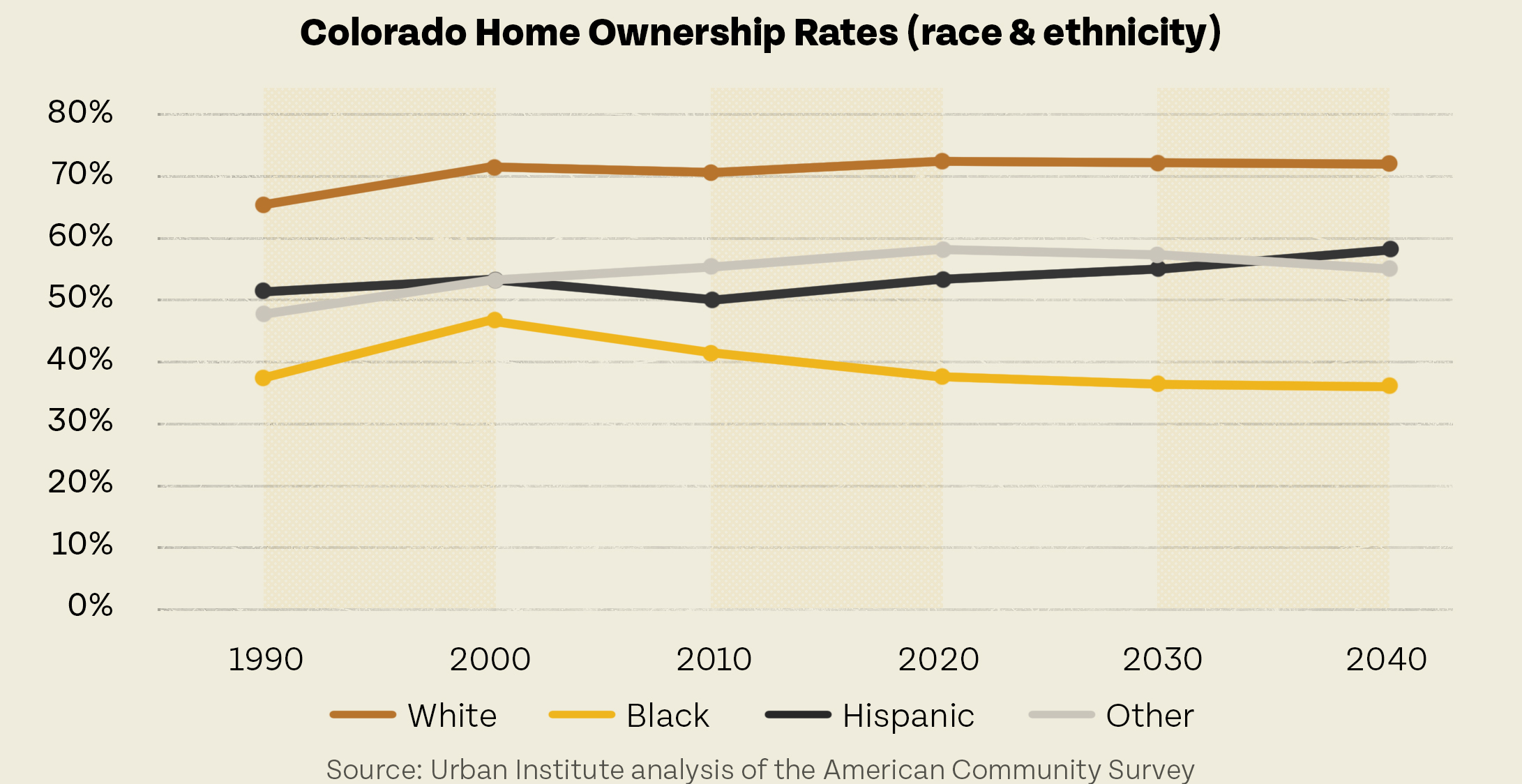

Homeownership, and consequently wealth accumulation, falls along racial lines in Colorado. While 71 percent of non-Hispanic Whites own their homes, just 51 percent of Hispanic households own their homes, and only 43 percent of Black households are homeowners. Although the gap has begun to narrow in recent years, it remains far too wide. Owning a home remains the primary form of wealth creation for Americans. The status quo only reinforces racial and economic inequality in our state.

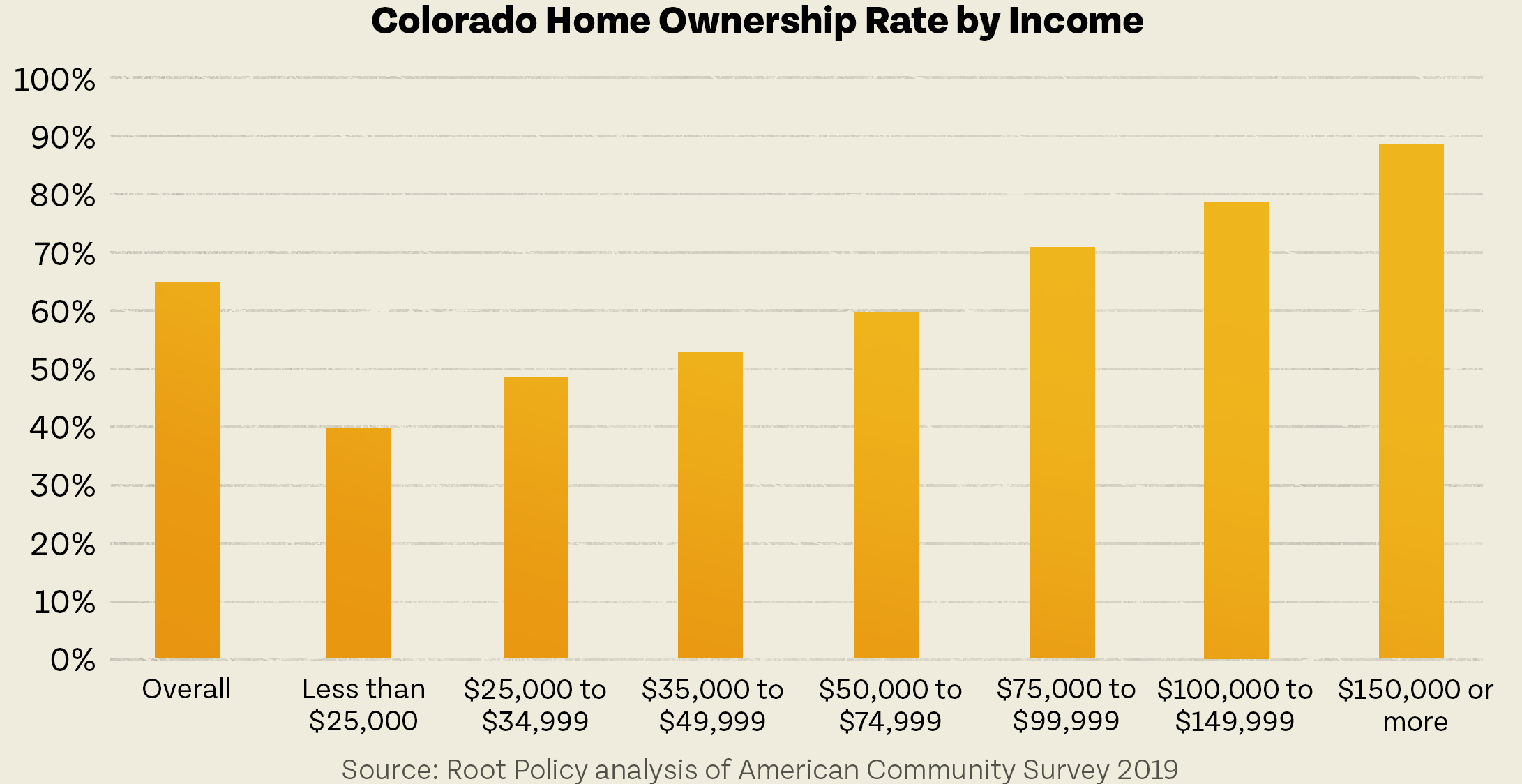

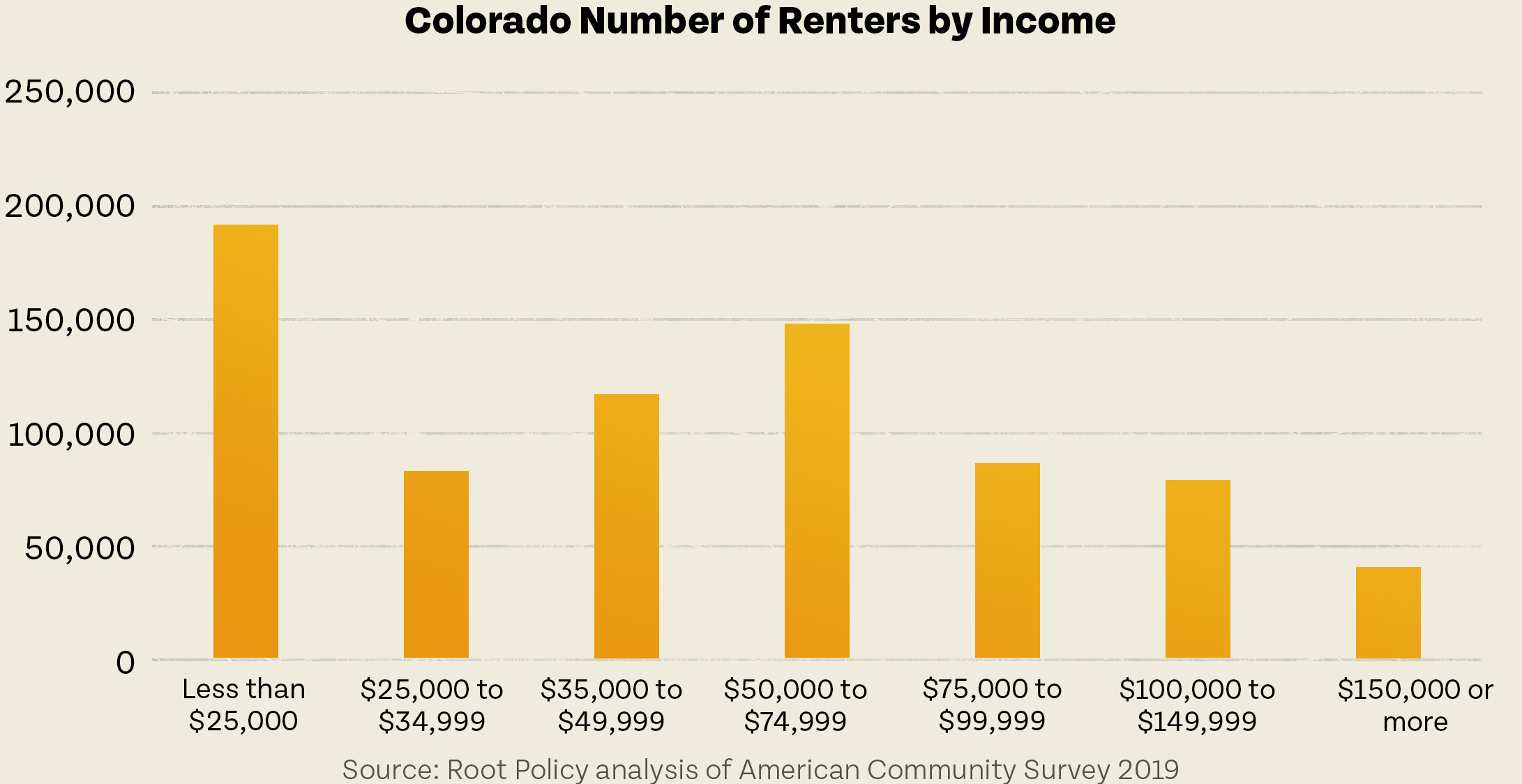

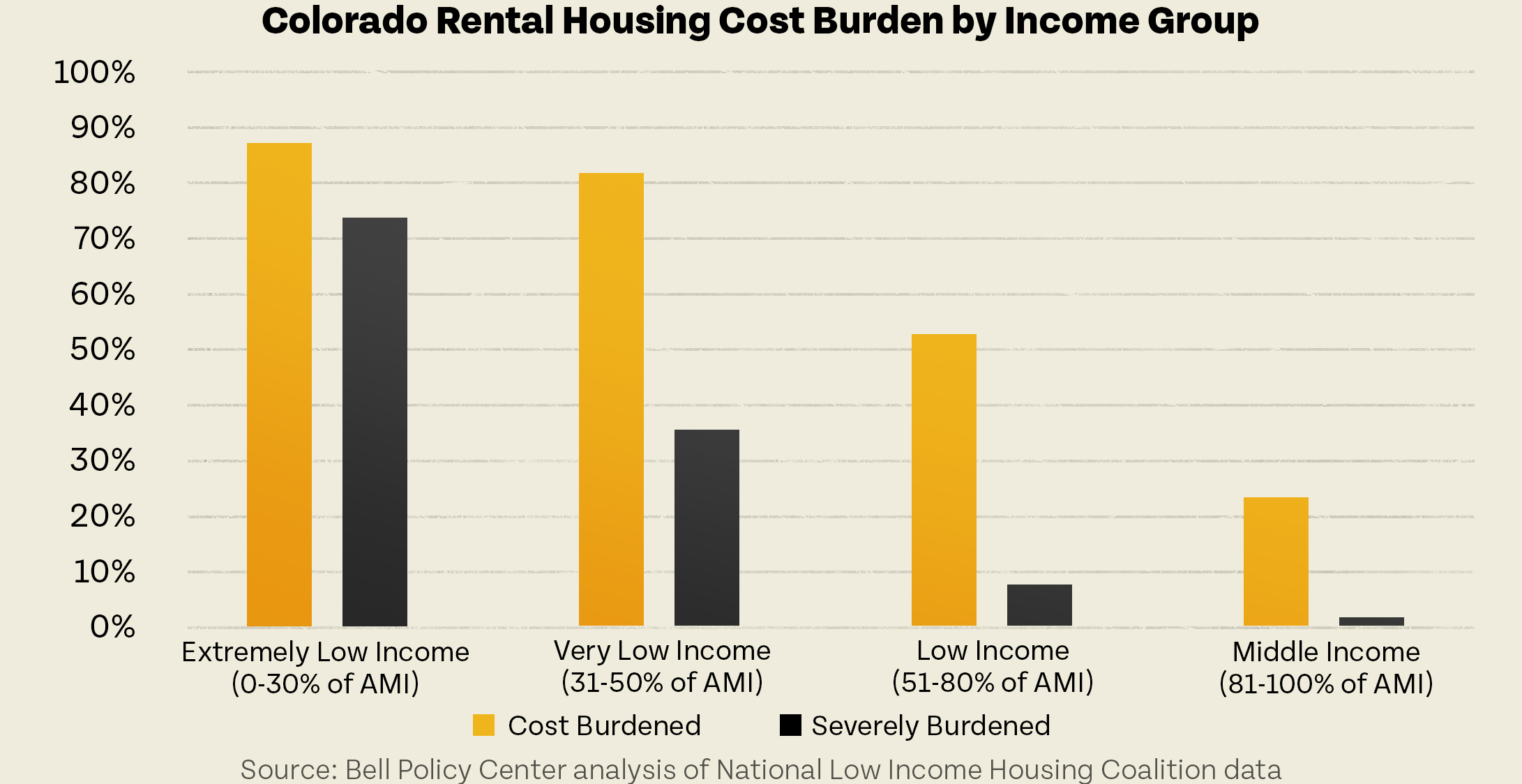

Unaffordable housing plagues all Coloradans, however, the plight is not uniformly shared. For those at Extremely Low Income (ELI), there are only 30 affordable and available homes per 100 renter households; at 50 percent of Area Median Income (AMI), 49; at 80 percent of AMI, 94; and at 100 percent of AMI, 103. This trend subdivides further among ELI Coloradans, 86 percent are cost-burdened (households spending 30 percent or more of their monthly income on housing) and 74 percent are severely cost-burdened (households that spend 50 percent or more).

Supply constraints

Along with increasing demand and greater unaffordability for many Coloradans, the state suffers from a severe housing deficit. Housing supply has lagged behind, with the number of new housing units built between 2010 and 2020 falling 40 percent. The State Demographer projects nearly 500,000 new housing units are needed between now and 2030 (or 40,950 units per year) to return the housing market to a healthy level. Likewise, they project an increase of 35,000 households per year between 2020 and 2030, slowing slightly to 29,600 per year between 2030 and 2040.

With population growth alone, the state cannot keep up with housing. Between 2010 and 2019, the state added 249,032 housing units while it gained 273,395 households. Meanwhile, the ratio of housing units to households fell from a high of 1.15 in 2006 to 1.09 in 2016; as of the latest available data in 2019, the ratio was only 1.11. Adding insult to injury, estimates contend half of the state’s vacant homes are for occasional, recreational, or seasonal use. A figure up from 40 percent in 2010. When adjusting for seasonal vacancies (based on five-year estimates), the ratio of housing units to households falls to a 2016 low of 1.05 that carried into 2019.

Adding to the housing supply deficit since the housing market crash in 2007, labor and supply chain shortages will add to the slowdown into 2022. Home builders have been unable to fill open positions or recover to pre-pandemic levels, while the cost of copper wire was up 156 percent (y/y) in October 2021 and lumber 129 percent (y/y). Construction costs were already high, having consistently increased since the 2007 financial crisis. Simply put, there aren’t enough homes in Colorado today and we need a massive amount of new housing–across all income levels–tomorrow.

Home Ownership Rates

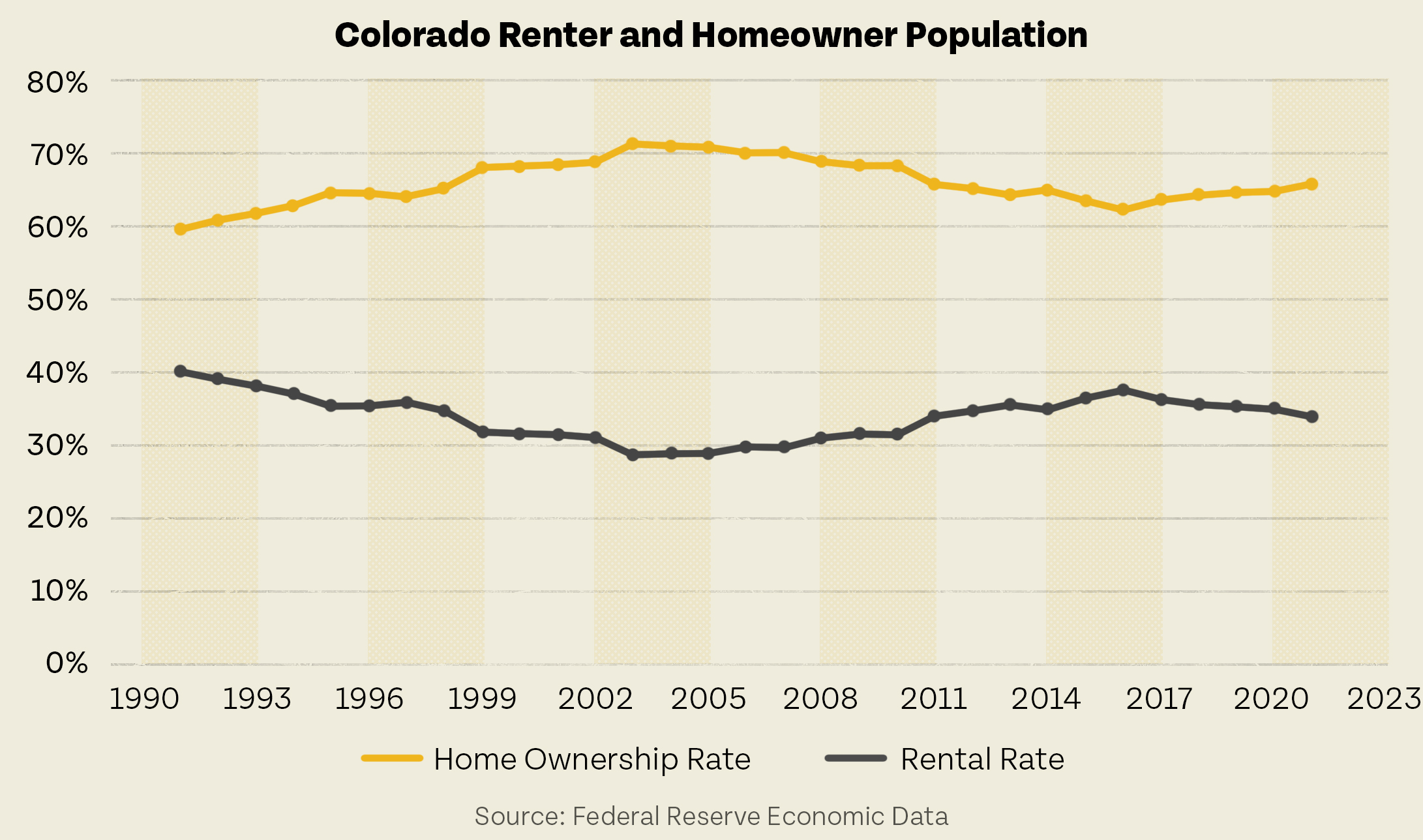

Across the country, home ownership rates have been in decline since their 2004 peak of 69.1 percent; today they sit at 65.4 percent, which is above the 50-year rolling average. The average in Colorado is slightly higher at 65.8 percent, down from a dramatic 2003 high of 71.3 percent. Like the housing supply, home ownership rates have remained lower since the crash, however, the pre-crash rates should be considered unusually high. In the heat map above, the counties with the highest rate of home ownership are Elbert (90 percent), Custer (87.2 percent), and Mineral (86.6 percent), whereas, the lowest rates are in Denver (49.9 percent), Alamosa (57.8 percent), and Bent (59.6 percent).

These homeownership rates are slightly distorting as more and more of the housing market has been bought up by large investment and real estate companies. The share of loans for second homes or investment properties remains dramatically high across all metro areas as well as the state overall. Rural mountain counties lead the way, such as Routt County where 47 percent of loans were for second homes or investment properties in 2019. In Larimer County, 14 percent of loans served these purposes compared to 11 percent for the state overall.

Recent studies demonstrate that single-family homes purchased by institutional investors face higher rent and fee increases — as much as 37 percent higher than the single-family average — as well as the diminishing quality of housing over time. Additionally, according to national data the five largest companies purchasing single-family homes more often purchase homes in Black majority neighborhoods. Their primary holdings are 40.2 percent Black majority whereas the Black population in the U.S. is 13.4 percent or three times less.

Despite the high demand for housing, this supply deficit pushes first-time buyers out of the market. Over the last 12 months, only 28 percent of home sales went to first-time buyers — a six-year low. This trend seen nationally can keep prospective home buyers in the rental market, placing even greater pressure on rental prices. Keeping would-be first-time buyers in the rental markets quells wealth accumulation as homeowners’ incomes are on average 82 percent higher than renters’.

Rental Rates

Conversely, rental rates in Colorado have risen slightly since the global financial crisis low of 30.9 percent. Today the state average is 34.8 percent, an increase that covers great variation across the state. The spread is wide with the counties of Denver (50.1 percent), Alamosa (42.2 percent), and Bent (40.4) leading the way as renter-heavy counties. On the other side, the lowest rental rates in the state are found in Elbert (10 percent), Custer (12.8 percent), and Mineral (13.4 percent).

More importantly than the rental rate in itself are the proportion of Coloradans who cannot afford the price levels they’re currently paying. Of the half of Colorado renters who are cost-burdened (spending more than 30 percent of their monthly income on housing), they are more often women, over 40, single parents, and/or without a postsecondary education. And as many as 13.3 percent of Coloradans are extremely cost-burdened, putting half of their monthly income into housing. Not surprising, then, is the trend of rents rising faster than incomes in Colorado counties/cities with more than 50,000 residents. This widening gap is most severe in Aurora, Boulder, Lakewood, and Westminster as well as Eagle County. In these areas, rent increases were as much as double that of income.

Short-term rentals also pose a challenging problem, as their proportion of market share has grown rapidly. This is especially true in mountain communities where short-term rentals have exacerbated the deficit of workforce housing. In Summit County, one-third of available housing units are being used as short-term rentals. Workers in mountain communities face increasingly long commutes as they’ve been forced to live further away from their workplaces. Regulations to limit short-term rental properties have faced roadblocks, although some cities have successfully increased taxes or passed caps on short-term rentals. In the coming legislative session, state lawmakers could consider a statewide cap as well as increasing the property tax assessment rate on short-term rentals, breaking them off as a separate category from residential properties.

At the aggregate level, homeowners remain the majority, however, this varies greatly across different counties. Renters, too often left out of the price relief debate, face accelerating rent increases, particularly among metro areas.

Going forward

In the 2022 legislative session, state lawmakers took important steps toward improving tenant rights for Coloradans and increasing the affordable housing stock. While state lawmakers and county officials consider necessary changes to land use and zoning to increase the housing supply, we must be sure our policy prescriptions match the many Colorados reflected in our deeply unequal housing market. When responsive, policies that mitigate the affordable housing crisis will have knock-on effects of reducing racial and economic inequality.