For-Profit Schools: Bad Actors in Higher Education

The predatory actions of certain schools, in particular for-profit schools, contribute to the amount of student debt accumulating and are constitutive of greater flaws in the higher education universe. In an environment that has been accused of feeling like it was “crafted to keep low-income…students out of college,” for-profit schools are furthering that narrative.

These schools target students of color, low-income, and other typically marginalized students with promises of post-grad prospects that tend to actually leave them worse off than never having attended at all. An alarming amount of these students graduate with valueless degrees, poor career prospects, and high debt. Most concerning is how for-profit schools typically advertise themselves, often trying to align with historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and appealing to marginalized demographics, exploiting racial and economic inequality for private gain.

For-profit schools are yet another indicator of flaws in the higher education ecosystem, those being the increasing devaluation of degrees and not approaching higher education as a public good. They are signs “of society’s willingness to make a high-cost, high-risk, debt-driven system of higher education absorb the demand among workers who — as almost every expert predicts — will increasingly have to go back to college many times to stay employable.” For-profit schools take advantage of the need for quick, credible education caused by changes in the workforce and have proven themselves faulty solutions.

For-profit schools are just that: a business to generate revenue, not necessarily an institution to provide a solid education for students. The biggest differences between for-profit schools and nonprofit schools is the former enrolls more nontraditional students, often manifest as online schools, and get most of their funding from tuition in the form of federal student aid programs. These schools are the most diverse by program and size, and were the fastest growing in the higher education sector until recently. Enrollment in private for-profit institutions grew swiftly from 0.2 percent to 9.1 percent of total enrollment in degree-granting schools between 1970 to 2009.

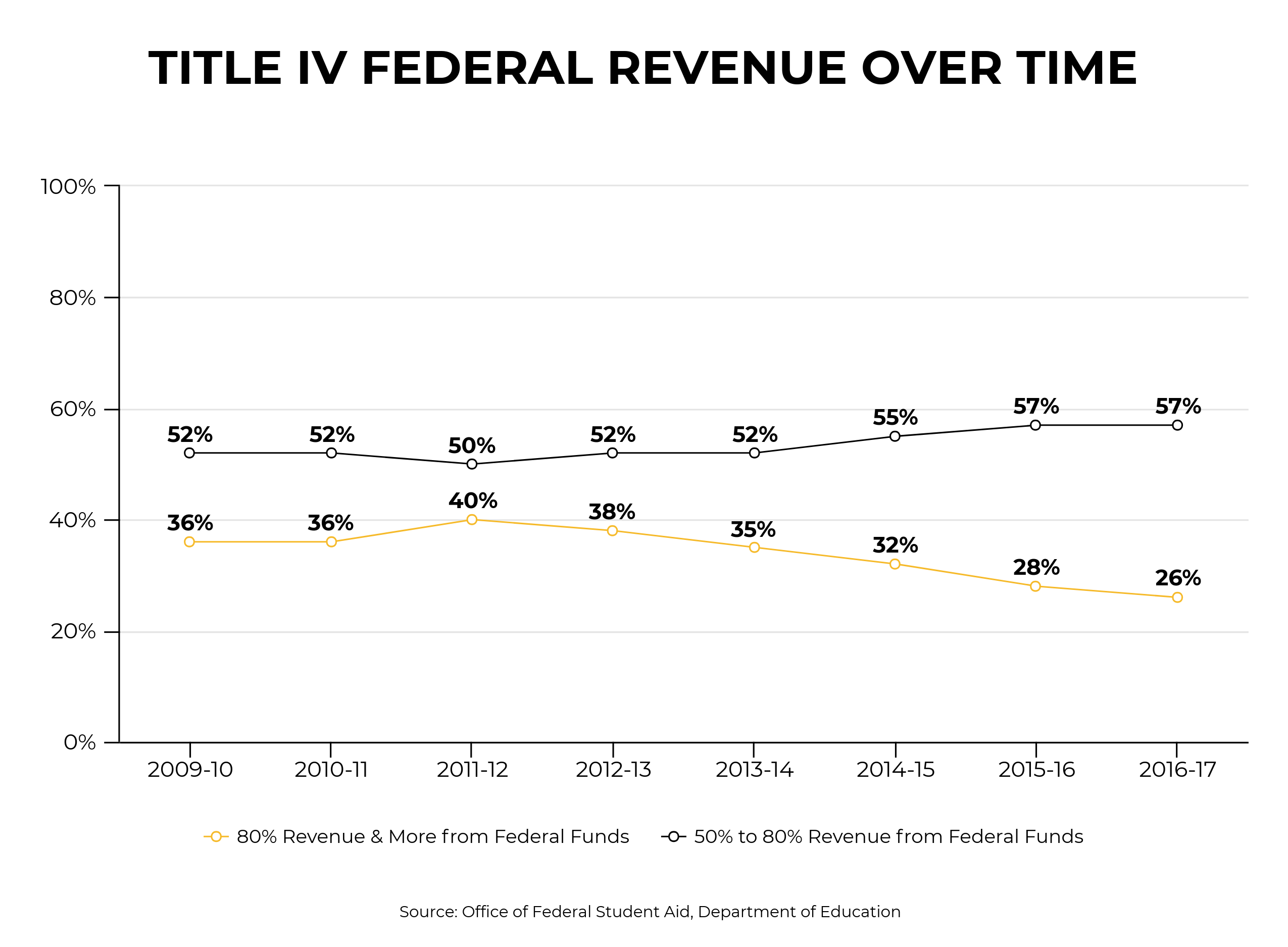

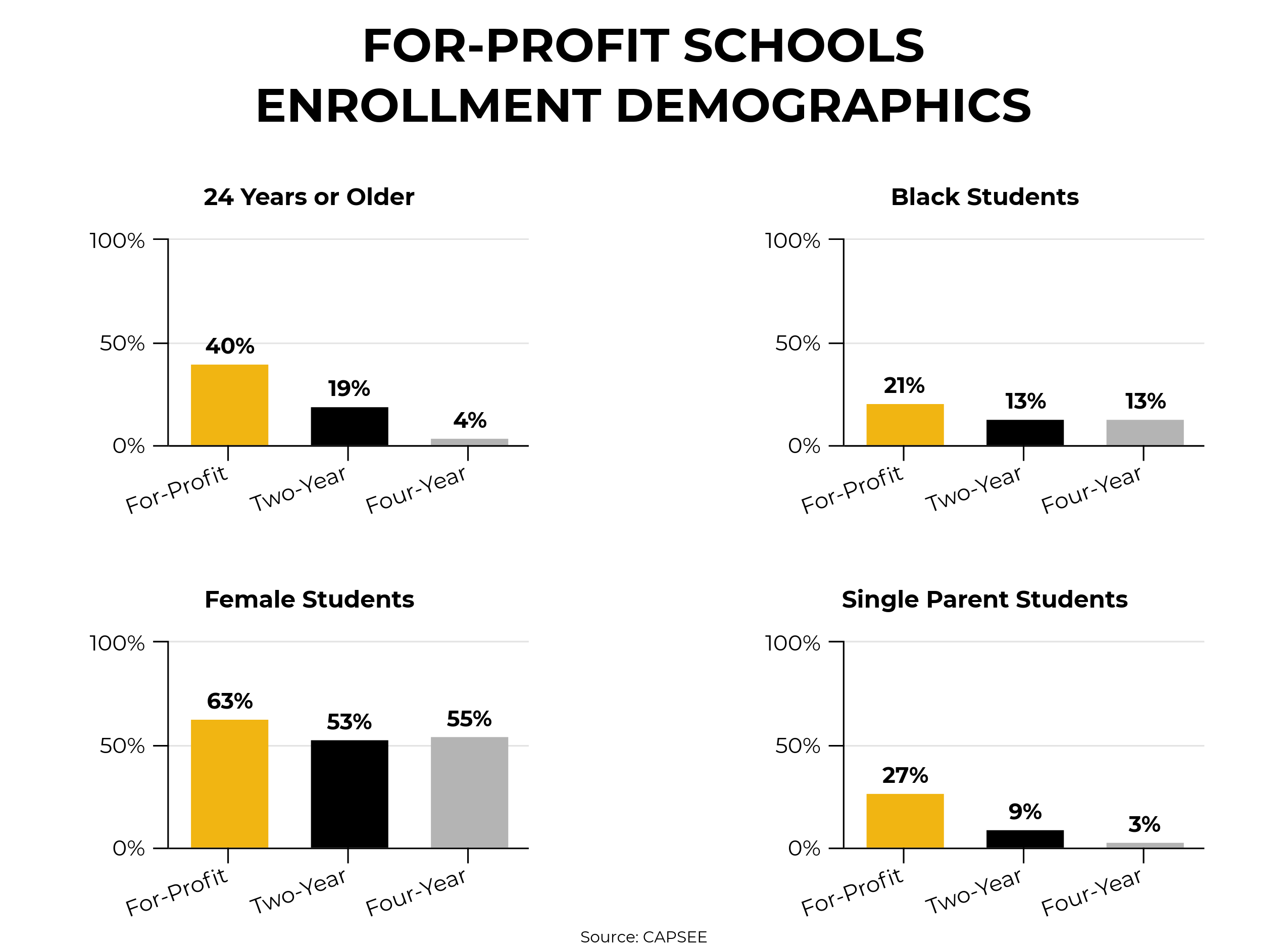

The design of for-profit schools necessitates substantial resources in the form of high tuition costs that come primarily from students and federal financial aid programs to go to extensive sales and marketing needs. About 26 percent of for-profit schools get at least 80 percent of their revenue from federal financial aid as of 2017. Because of the lack of regulation and lack of public investment, for-profit schools have little incentive to look out for students if revenue continues to come in. Even worse, the dependence on federal aid means for-profit schools pursue students who qualify for the maximum amount — students who also happen to be some of the poorest. For-profits schools enroll more students of color — particularly black students — women, older students, and single parents than any other type of school. Black people account for 13 percent of all students in higher education, but make up 22 percent of those in for-profit schools. Sixty-five percent are women and 65 percent are 25 years and older, opposed to just 31 percent at four-year public schools.

For-profits schools enroll more students of color — particularly black students — women, older students, and single parents than any other type of school. Black people account for 13 percent of all students in higher education, but make up 22 percent of those in for-profit schools. Sixty-five percent are women and 65 percent are 25 years and older, opposed to just 31 percent at four-year public schools.

Students attending for-profit schools are less likely to have graduated from high school as well. Seventy-six percent of students at for-profits had a high school diploma in 2011, as opposed to 86 percent and 96 percent at two-year and four-year colleges respectively. Currently, the average cost of attendance at a for-profit — $16,000 — falls only second to that of private, four-year colleges, $27,300. In 2014, a two-year for-profit college cost on average $14,193, compared to $3,370 at a typical public community college. It follows students who attend more costly for-profit schools also end up with higher amounts of debt. Unfortunately, there is very little data on the amount of debt graduates of for-profit schools accrue, because these schools typically don’t answer surveys due to the controversial nature of their operations and performance.

It follows students who attend more costly for-profit schools also end up with higher amounts of debt. Unfortunately, there is very little data on the amount of debt graduates of for-profit schools accrue, because these schools typically don’t answer surveys due to the controversial nature of their operations and performance.

In 2014, 96 percent of for-profit graduates left with debt. The most recent, and somewhat more comprehensive, data is from the class of 2016 graduates. Of them, 83 percent took out student loans; the average amount being $39,900, 41 percent higher than the debt held by graduates of every other type of school.

Thirty percent of those who started at a for-profit school defaulted on their loans within 12 years of entering college, compared to only 4 percent at public colleges and 5 percent at nonprofit colleges. While students at for-profit schools make up only 13 percent of all college students, they comprise almost half of all defaults on federal student loans.

Furthermore, graduates of for-profit schools actually tend to do worse in the labor market than with just a high school diploma. In 2014, 72 percent of graduates from for-profit schools made less than high school dropouts. Altogether, graduates of public undergraduate certificate programs earn $9,000 more than the mean earnings of their counterparts at for-profit schools. Additionally, students at for-profit schools generally see a decline in earnings five years to six years after graduating, as their credentials are often 30 percent to 40 percent more expensive than the very same ones at other institutions, saddling them with job prospects than cannot help pay off the debt they took on to avoid this very situation.

For-profit schools also produce graduates with such high amounts of debt due to a series of issues that contribute to other struggles after graduation. The predatory nature of these institutions has come to light by discoveries of their high tuition costs, low graduation rates, poor career prospects, and high debt loads.

Corinthian Colleges Inc. was the first company identified for defrauding students on a massive scale. Corinthian Colleges was a large conglomerate of postsecondary, for-profit colleges that was investigated and accused of misrepresenting job placement rates to students in 2014. A review by the Department of Education found 947 instances of falsely stated placement rates, fining the company $30 million. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) sued Corinthian Colleges for pressuring thousands of students to take out their own private, high-cost Genesis loans with the promise of what turned out to be phony job prospects and career services. Corinthian Colleges then used illegal, predatory methods to collect on the loans while students were still in school.

More recently, a Christian nonprofit named Dream Center was approved by the Department of Education to acquire a chain of struggling for-profit schools. Barely a year after the purchase, many of these schools have shut down, with more expected to follow. The schools affected include Argosy University, South University, and the Art Institutes, with 26,000 students among them who were suddenly locked out of classrooms, told not to bring anyone to graduation, and had no way to transfer their credits. Expected profits of $30 million actually ended up as a $38 million loss for Argosy. However, despite being told to repay students the extra money they borrowed, Argosy schools never followed through.

Dream Center was able to take over these schools so easily because of a complete shift in regulation of for-profit schools once the new administration took over in 2017. Throughout his presidency, President Obama made significant strides to regulate for-profit schools, most notably the gainful employment rule. The law required most for-profit schools to appropriately prepare students for “gainful employment in a recognized occupation.” This set students up for a job where their annual loan payment would not exceed 8 percent of their total earnings. Schools that didn’t abide by this rule would lose their federal student aid, which meant almost guaranteed closure regarding for-profit schools.

Since her takeover, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos has systematically dismantled many Obama-era safeguards designed to protect students against predatory schools. The gainful employment rule was first priority, but is still in place at least until 2020. DeVos has also quickly undone a special team of investigators assigned solely to review misconduct by for-profit schools in advertising, recruitment practices, and job placement claims. It’s important to note than since entering office, DeVos’s top hires all primarily have backgrounds in the for-profit sector.

Revenue is the driving force and incentive of for-profit schools; without funding, they would almost immediately go under, as would any business. As such, these institutions do what they must, and operate under a guise of meeting the needs of underserved students. For-profit schools target low-income and minority students in the name of combating racial and social inequality when, in fact, they exacerbate these issues.

This concerning trend stems from a key concept: As technology advances, human labor isn’t as necessary as it used to be, which means less financial security. The more pressure people feel to ensure themselves against automation, the more likely they are to return school in pursuit of higher credentials. The people who are most at risk of this instability and with less access to tools of mobility are women, black people, poor people, and others systemically oppressed in our society.

These are the people targeted by for-profit schools. Before their downfall, Corinthian Colleges spent over $600,000 over only two weeks for advertisements on BET (Black Entertainment Television). Many for-profits try to appeal to black students by aligning their missions with those of HBCUs — a mission to increase educational opportunity for black students. In 2011, Ashford and the University of Phoenix graduated more black students than any other higher education institution in the U.S., but left them with “essentially the same grim job prospects as if they had never gone to college, plus a lifetime debt sentence.”

In 2015, black and Latino students made up less than one-third of all college students, but accounted for almost half of all private, for-profit students. Eighty-nine percent of Latino and 90 percent of black students borrowed for a bachelor’s degree, with their debt averaging out at $40,000. About 70 percent of black students who borrow at for-profit colleges default within 10 years.

What's Happening in Colorado

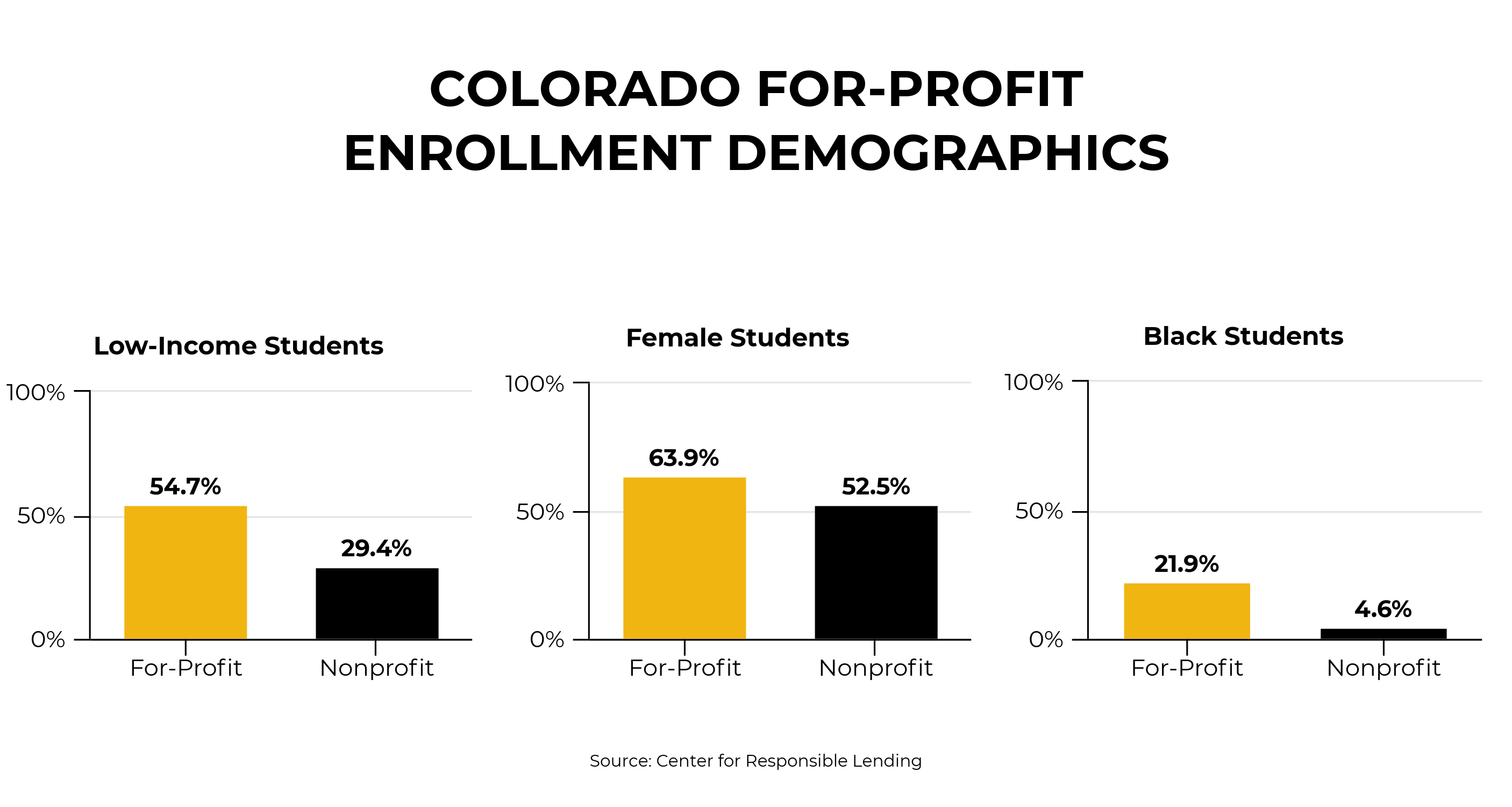

The same trends are reflected in Colorado. As of 2018, Colorado for-profit schools enroll disproportionately more women, black, and low-income students than other schools in the state. About 28 percent of students graduate from for-profit schools opposed to a little over 46 percent from public, four-year schools. Almost 55 percent of students at for-profit schools borrow to afford attending, more than students at private and public four-year schools. Consequently, these students have significantly more debt, a median of $30,799 compared to $21,453 and $25,039 at public and private four-year schools, respectively. Finally, students at Colorado for-profit schools are three times as likely to default on their loans.

About 28 percent of students graduate from for-profit schools opposed to a little over 46 percent from public, four-year schools. Almost 55 percent of students at for-profit schools borrow to afford attending, more than students at private and public four-year schools. Consequently, these students have significantly more debt, a median of $30,799 compared to $21,453 and $25,039 at public and private four-year schools, respectively. Finally, students at Colorado for-profit schools are three times as likely to default on their loans.

Colorado’s own Technical University and American InterContinental University had their parent company, Career Education, settle on charges of fraud that included using inappropriate language to pressure students into enrolling; obscuring the total cost of enrollment by only disclosing the cost per credit hour; lying to students about being able to transfer credits; and inaccurately representing job placement prospects, accreditation, selectivity, and graduation rates. $493.7 million in student debt was cancelled for 180,000 former students, but thousands more across the country still haven’t seen anything from their time at a for-profit school. Still more, cancelling the debt of students defrauded by for-profit schools is merely a band-aid to the bigger problem. Re-establishing regulations and oversight on the federal and state level is necessary to hold these institutions accountable.

For-profit schools are yet another symptom of the flawed narrative of guaranteed economic and social mobility derived from higher education. These institutions inherently exploit and take advantage of the claim that all education is good education. In a society that is firmly rooted in inequality, for-profit schools constitute and are constitutive of those inequalities, simultaneously compounding risks to marginalized groups and perpetuating the student debt crisis.